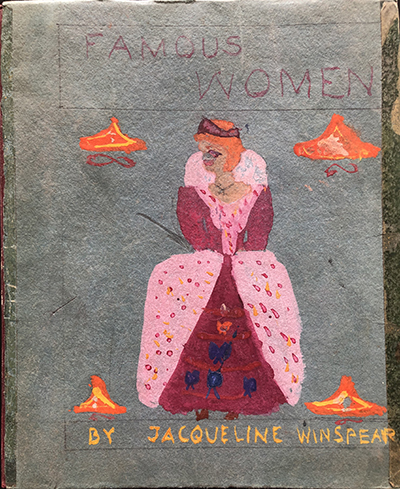

I’ve always been interested in the history of clothing and costume – note, I’m avoiding using the word “fashion” here. As I grew into my teen years, I raided clothing tucked away at the back of my mother’s wardrobe – a few “Before I was married to your father” garments that were purchased long before a time of throwaway fashion. I also haunted vintage clothing stalls at Kensington Market on those rare occasions my pal Anne-Marie and I managed to persuade our parents to let us go up to London alone for the day. It was a bit of a hippy gathering place, after all.

The old Kensington Market

The old Kensington Market

Unlike today, at a time when the fashion industry is cited as the biggest polluter on the planet, back in the day people (ordinary folk, not the better heeled in society) would save for a long time to buy clothing – a new coat, for example. It had to be a “classic” choice to last you a good long time. I’m still like that, though I’ve had my insouciant moments. Yes, the leather biker jacket. Always wanted one. Bought one only to admit to myself that I don’t like the feel of leather next to my skin. I should have known better on so many levels.

I added this pic to torment myself

I added this pic to torment myself

One of my favorite pieces from the back of Mum’s wardrobe was a coat she continued to wear until the early 1960’s. She called it her “New Look” coat. In fact, she often pointed out that she had been the first young woman in her neighborhood to wear the “New Look.” Of course, it wasn’t THE New Look, but a copy of a coat in the style of the famed Christian Dior collection. She had saved up her money and clothing coupons for a long time to buy that coat, and by the time she carried it home, of course women in the wealthier parts of London had been wearing the New Look for a while. I loved that coat – it was made of soft black woolen fabric, lined in satin and with a nipped-in waist. The rounded shoulders – just the hint of shoulder pads – draped down to sleeves finished with a buttoned cuff and the soft collar lay in an attractive silhouette around the collar bones. My mother was taller than me (I’m not short, but she comes from a family of Amazons), so I wore the coat with a wide black belt to hitch it up a bit, and black boots handed down from a cousin, topping off my “look” with a cream beret. I thought I looked really chic, until my brother said I looked like a Cossack, and everyone would stare at me if I walked through our small town dressed like that. Well, that’s brothers for you – but truth be told, he had a point. Yet the more I pored over books on clothing trends through the ages, the more I fell in love with Christian Dior’s New Look and hoped it would come round again. My mother always told me to hang on to clothes because fashion “comes round again.” It does, though always just a bit different the next time. But to understand why Dior’s New Look made such a splash, we have to go back to wartime.

Ready for work in wartime

Ready for work in wartime

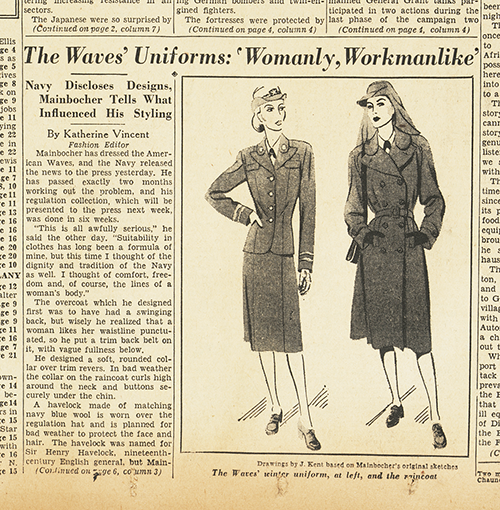

Clothing was rationed in WW2 Britain and of course across Europe. In addition to saving money, you had to save clothing coupons. It was well documented that when a woman was getting married, if she wanted to wear a gown, then the whole family and half the neighborhood had to chip in their coupons. It is said the same thing happened to Princess Elizabeth when she married in 1947, though it brings a smile to imagine Queen Mary handing over her coupon book and saying, “There you are love, treat yourself to something nice.” There were textile shortages throughout Europe during the war (though there’s an interesting story of how the Germans were persuaded to allow the Parisian clothing industry to continue – a tale for another time perhaps). Many famed couturiers left France for either the US or Britain. It’s important to note that there is a distinct difference between “couture” and “designer” – in those days, as now, you had to be stinking rich to afford couture, and the word “designer” didn’t really come in with a flourish until the ready-to-wear industry took off. But it was the well-established ready-to-wear industry in America that led many of those French couturiers to cross the Atlantic. Main Rousseau Bocher – known as “Mainbocher” – was one of those couturiers. He went on to design uniforms for US Navy “Waves.”

Mainbocher for the US Navy Waves

Mainbocher for the US Navy Waves

During the war, fashion became very structured, almost aggressive in the look. The influence of uniforms on women’s wear is easy to identify in old photographs of the era. Furthermore, throughout the centuries, women’s clothing has indeed shown some aggressive features during a time of war – shoes often become pointier as if emulating weaponry. Shoulder pads were definitely “in” during WW2, and in wartime austerity Britain, a line of “Utility” clothing was launched. Hemlines went up, the width of skirts was narrowed, the number of pleats and pockets were restricted and limitations were placed on the number of buttonholes. This was all to save fabric – and the fact that many clothing factories were turned over to wartime needs. At the same time “Make Do and Mend” became the order of the day. Overall, despite the influence of Hollywood, women’s clothing became more masculine and functional. Eventually the war ended, but rationing went on.

Utility Clothing in Britain

Utility Clothing in Britain

Then in 1947 Harpers Bazaar featured the launch of Christian Dior’s “New Look” with a model wearing what became known as the “Bar Suit.” Interesting – because in Britain a woman’s skirt or dress and jacket set was called a “costume.”

The New Look is launched with the “Bar Suit”

The New Look is launched with the “Bar Suit”

The Bar Suit was a revelation. The full skirt (no fabric spared there) hit at low calf length, and the jacket had a soft shoulder-line and a flat collar and a narrow waist. It flew in the face of austerity, rationing and wartime, and heralded a golden age of women’s fashion. Even today I think it’s utterly gorgeous and would give anything to wear it! Mind you, food rationing rendered many women slender enough to carry off such a look. When I was sixteen I remember asking my mother if she ever dieted when she was my age – that was the wrong question. “It was all I could do to get enough to eat when I was your age, so don’t let me hear the word ‘diet’ again!” she said.

Every woman wanted the New Look, that chance of elegance during a time of extreme hardship. Of course all but the privileged few were still struggling to put a decent meal on the table – but deprivation doesn’t stop you dreaming. For those of you who haven’t seen either the original film Mrs. ’arris Goes To Paris with Angela Lansbury, or the more recent incarnation with Lesley Manville (though the “H” is reinstated), watch it for what the New Look meant back in the day.

The Bar Suit, again!

The Bar Suit, again!

But just to give you some perspective, the taffeta dinner dress from the same collection used some 25 yards of fabric. Wow! Think of the ration coupons you’d have needed for that!

The Dinner Dress

The Dinner Dress

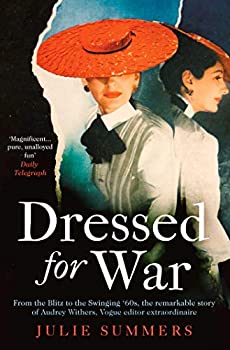

Anyone interested in this subject would enjoy Dressed For War by Julie Summers. It recounts the development of the British Edition of Vogue (“Brogue”) during the war – and shines a light on a fascinating period of social history. Until the war, Brogue reflected the American edition, however, in the early years of the war, before Pearl Harbor brought the US into the conflict, British readers became dissatisfied with features that had no bearing on their lives and the deprivation and terror they faced, so British editor Audrey Withers began to chart a new course with more home grown content. She also expanded subject-matter to include international war news from the female perspective. Withers gave wartime journalist Lee Miller her big break.

You may wonder what happened to that lovely New Look coat I used to wear. Well, in his early 20’s my brother had a weekend sideline with a friend, running a stall selling vintage clothing at Camden Lock market in London. At around the same time I had my own weekend gig helping a pal with a stall on Portobello Road market, only we were selling Art Deco jewelry, pottery and china. One day I was visiting my parents and I asked, where my New Look coat was. I couldn’t find it in the wardrobe. “Oh, that old thing?” said my mother. “Your brother took it to Camden Lock and sold it. I didn’t think you would want it anymore.”

I was heartbroken. But at the end of the day, it’s only clothing, “old tat” as my mother would have said, and I probably did look like a Cossack. Yet to me that coat was special. It was history to wear, and I still miss it.

And to sign off – here’s a stunning WW2 photo by Cecil Beaton, showing the model in a costume by Digby Morton.