Many of you will remember that some years ago I began a blog dedicated to women’s history, women’s lives and women’s accomplishments. My intention was to focus on the little known heroines of the past and present—with many of those heroines being women who went about their lives without ever thinking of themselves as anything but “ordinary.” After a while family responsibilities began to take more and more of my time, along with my work as a professional writer, so the blog was pushed to a back burner and eventually taken offline. But I missed writing those pieces and wanted very much to revisit it at some point, though I thought I needed another name. Which brings us to this, the launch of the WomenSong.com blog.

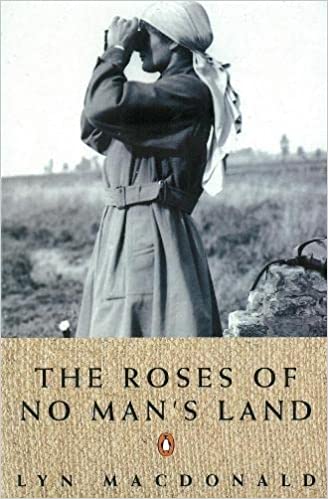

I have been wondering how to begin again, what I might write about in this new inaugural post, then a few days ago I was browsing the stacks of a wonderful “used” bookstore close to my home, and came across a copy of The Roses of No Man’s Land by brilliant military historian, the late Lyn MacDonald. MacDonald wrote extensively about the Great War at a time when veterans of that war were still with us and able to be interviewed—her diligent research, insight and humanity led to a number of incredibly detailed but very readable books on the war to end all wars. The Roses of No Man’s Land focused on the work of wartime nurses and medical staff. I first read it soon after it was published in 1980, and picked it up again when I began writing Maisie Dobbs.

With The Roses of No Man’s Land in mind, my first blog post will be about nurses.

My respect for nurses began in childhood, as it does for many kids who spend time in a hospital. I have such a soothing memory of the nurse who bathed my eyes every morning following eye surgery. Anyone who has had such a procedure knows that it’s hard to open your eyes in the morning because they’re a bit gummed up. I looked forward to hearing the nurse come into my room, the sound of her setting down her bowl of warm water on the side table and then dipping cotton wadding into the water. She would remove the pads from my eyes and with a gentle touch bathe away the nighttime gumminess until I could focus again. Years later I volunteered at a school for children with physical disabilities. Many kids were in wheelchairs or walked with crutches, or they had twisted spines and feet. I remember spending some time with a band of little girls and every single one told me she wanted to be a nurse at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London—probably because at one time or another every child in the school had spent time at that famous hospital for children. Children instinctively know that the most important people in the hospital are the nurses.

An early image depicting Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) when it was known as The Hospital for Sick Children.

The role of tending the wounded during a time of war has fallen to women since earliest times. I visited Battle Abbey in Sussex a year or so after Maisie Dobbs was published. The Abbey was close to my parents’ home, yet I hadn’t visited since childhood. Of course the whole “visitor experience” had become very sophisticated, with audio tours available. I remember standing at the bottom of the hill where the battle between the army of William of Normandy and King Harold had taken place in 1066; I was listening to the audio tour narrator describing the terrible wounds inflicted by arrows and swords and how local women were on the battlefield, going to the aid of the wounded. “Some things never change,” I thought.

Nurses in the American Civil War.

There was a time when nurses were depicted in film and books as either a doctor’s romantic interest or something akin to the fearsome “Nurse Ratched” of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In Britain the “Carry On” series of comedy films played up the lecherous doctors pursuing stunning nurses, only to be thwarted by the Matron, usually played by actress Hattie Jacques.

Hattie Jacques as Matron.

One thing was definitely true—back in the day, woe betide any young doctor who managed to get on the wrong side of Matron! I think they could have done with her to sort out the guys in MASH.

One of the first books I read that seemed to explore the levels of PTSD found in nurses who had worked in war zones, was the book Nam by Mark Baker. While names weren’t mentioned in the book, the story followed veterans from basic training to coming home—and one of those veterans was a nurse who described something that happened years later, when she had a couple of children and was living a settled family life. A helicopter flew low over the house, and in an instant she dropped everything and ran outside, her head low as it would have been when she had to run toward medivac helicopters in Vietnam ready to receive wounded. The woman’s kids came running out after her, wondering what the heck was going on.

Nurses in Vietnam

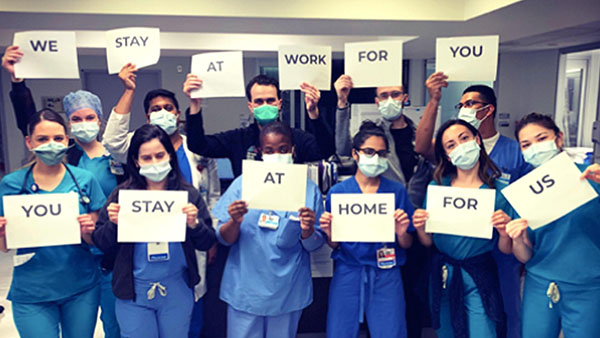

In the past two years of the Covid pandemic, the pressure on nurses around the world has been phenomenal—they have worked long shifts around the clock with barely a break. It broke my heart when I read about a nurse in England who had come off duty late at night following a long shift that had started early in the morning. She was exhausted and hungry, and when she stopped at a late-opening grocery store, she discovered that it was almost out of everything there was to eat—remember when people were stocking up and supermarket shelves were empty? She broke down in the store. We’ve all heard similar stories over this period of time—many of us know nurses who have been on the front lines of the pandemic war, and we are stunned by their fortitude, kindness and humanity. And of course many nurses are male—nursing ceased to be an all-female profession decades ago.

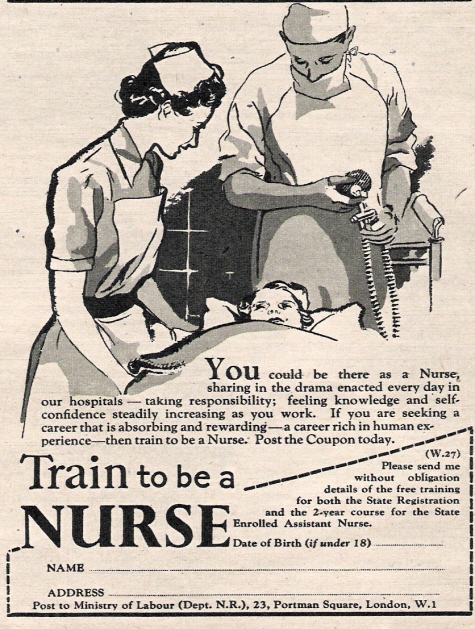

Now of course nursing is facing something of a crisis. The baby boomer generation who came into the nursing profession in droves is retiring, and reports suggest that there are not enough young women and men entering the profession to balance the loss. According to the World Health Organization, some 27 million women and men make up the worldwide nursing and midwifery workforce—over 50% of all health workers worldwide. 70% of all health workers are women. Given the numbers being lost, it is indicated that the communities most in need of nursing support will be the first to lose it.

Finally, if you are ever in the area around Cannon Beach in Oregon, hop along to the Lost Art of Nursing Museum, an amazing collection built up by Melodie Chenevert—it’s a wonderful place to visit.