In 1977 my brother, 17 at the time, was at a college not far from the flat I shared with my pal, Corinne, so he sometimes came to visit us (and be fed). One day we were walking along the street, when a girl about his age caught his eye. “That girl is so beautiful,” he said—and he was right. He plucked up courage and crossed the road to chat her up. She agreed to go for a cup of tea with him and I was left with the shopping bags.

But here’s something I noticed—the girl had no arms, just “flippers” where her arms and hands might have been. She was what was then called a “Thalidomide baby.” When my brother came home he told me the girl was “really nice” yet she had a boyfriend she was “sort of” seeing, and he was busy with college anyway but they’d had a really nice time. Oh, the bittersweet ache of the teenage crush.

I was recounting the story to a friend recently, and was a little surprised when the friend asked, “What’s Thalidomide?” Then I remembered—apart from a few cases, America was spared the Thalidomide “epidemic” that caught doctors completely unaware in the UK, Canada, Australia, Germany and Japan (the most impacted countries) during the late 1950’s and early 60’s. That American women were, for the most part, spared this terrible drug was all down to a remarkable woman, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, a scientist with the Federal Drug Administration. But just in case you’ve never heard of Thalidomide or the good doctor, here’s an overview of what happened.

Dr. Frances Oldham Keyes

Dr. Frances Oldham Keyes

Pharmaceutical companies are always under pressure to discover the next big drug development opportunity—the solution to a human problem. Sometimes the problem is one men and women have endured for years, and when the medication comes along, they are beyond grateful. For many women, one of the most difficult conditions to endure is morning sickness during pregnancy. Some women experience the most intense form: Hyperemesis Gravidarum. A friend suffered this level of sickness and she said it was the worst thing ever—she could not move without losing the last meal, felt a constant debilitating nausea, and was admitted to hospital several times throughout two pregnancies. I recall my mother being horribly sick when she was expecting my brother. The doctor wanted to prescribe “something new” but she made a ginger drink instead. Ginger was my mother’s go-to medicine for every stomach ailment.

The drug Thalidomide was first developed in (then) West Germany by the pharmaceutical company Chemie Grünenthal, GmBH. Originally marketed as a cold remedy and/or sedative, it was soon discovered to be excellent for ending morning sickness. And they were off to the bank! But the interesting thing about this invention, is that it has roots in the terror of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.

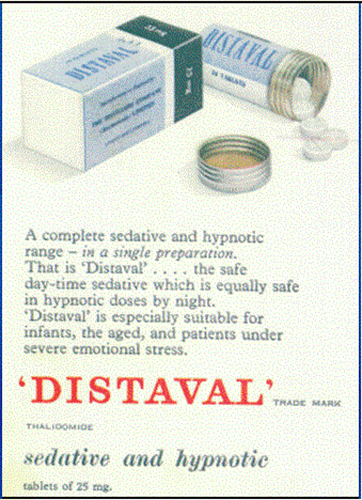

Thalidomide was marketed as “Distaval” in the UK, and touted for sleep and sedation, as well as morning sickness.

Thalidomide was marketed as “Distaval” in the UK, and touted for sleep and sedation, as well as morning sickness.

In the years following WW2, a number of scientists who honed their craft with experiments on human beings in the death camps, found a welcoming employer in Grünenthal. Otto Ambros—who invented Sarin gas—had been convicted of mass murder at the Nuremburg Trials, but was freed and ended up on the Thalidomide advisory committee (and this was after working in the US chemical industry). Other scientists who had experimented on inmates in the camps were also involved in the development of Thalidomide and according to a Scientific American report, it was another Nazi, Heinrich Mückter, who pushed the drug into production without adequate testing, so he could land the big bonus. Someone should write a book about the damaging effects on society of big bonus promises (and how those people support the idea of small government, because it’s easier to get approvals when there’s no one like Dr. Kelsey around to rock the boat).

Photos of Otto Ambros and Heinrich Mückter

The application to approve Thalidomide in the USA landed on the desk of Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey in 1960. The company with the US contract had a warehouse full of the stuff, and was anxious to get it out to consumers. Kelsey, just one month into her job, looked at the information and immediately gave it a big fat “No.” She rejected the application as she was not convinced by the evidence attesting to its safety. And she was right. I remember during my childhood seeing children with missing limbs, children who had a foot where an arm should be or hearing about another woman whose baby had been stillborn and deformed in some way. Distribution of Thalidomide to pregnant women would become an international disaster, with doctors rushing to identify the common cause.

Thalidomide Baby

Thalidomide Baby

Dr. Kelsey had been involved in stalling production of another drug as early as 1937, when she was a graduate student, part of the team working with Dr Eugene Geiling at the University of Chicago. They were investigating a common pharmaceutical at the time, used to treat infections: “Elixir of Sulfanilamide.” It was taken in large doses and tasted pretty disgusting, so to make it palatable to children they added a cherry-tasting solvent. Trouble was, that solvent was also known as anti-freeze.

According to The Smithsonian, in her memoir, Kelsey highlights weaknesses at the FDA during her tenure at the time—shortage of properly trained staff, part-time contracts, underpayment and a few medical reviewers who were “sympathetic” to the pharmaceutical industry. Apparently, “The most troubling deficiency in the process was the 60 day window for approving or rejecting drugs: If the 60th day passed, the drug would automatically go to market.”

The to-ing and fro-ing of inquiries and responses between Kelsey and Richardson-Merrell, the company pressing for the go-ahead to market Thalidomide in the USA (under the trade name “Kevadon”) is fascinating, because every time she flagged a problem or asked for clarification regarding testing, they came up with another advantage of this wonder drug or they pushed back by questioning her qualifications; whatever it took to get the approval because they just wanted to sell it. Richardson-Merrell criticized her work, they tried to go over her head and they pulled every trick in the book. But she stuck to her guns because one of her key concerns was the “neurological toxicity” listed as a side effect—at this point the company was touting the drug as a cure for inflammation. That’s when Kelsey wondered what might happen to a pregnant woman who took something that causes neurological toxicity—what would it do to the fetus? Good question.

The mal-formed feet of a “Thalidomide baby.”

The mal-formed feet of a “Thalidomide baby.”

Unfortunately the drug had already enjoyed some distribution in the USA. Richarson-Merrell was giving advance samples to 1000 doctors to hand out to patients, so by the time the company pulled the plug because they kept hitting a wall named Frances Oldham-Kelsey, there were 17 cases reported of malformed limbs on newborns.

As a result of the withdrawal and subsequent international outcry regarding Thalidomide, Congress passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendment, which required more oversight for clinical studies of drugs before granting approval. For her part, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey received the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service from President John F. Kennedy, making her the second woman to receive the high civilian honor.

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey and JFK

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey and JFK

Kelsey, who saved America from the scourge of Thalidomide died in 2015 at the age of 101.

Whenever I read something about Thalidomide, I remember my teen brother’s crush. She walked with a proud demeanor and was waving to a group of friends when he saw her across the street. I can only imagine how her parents must have felt at her birth, when they wondered how she would overcome the challenges facing her as she grew up—yet it was evident they had given her the confidence to walk tall, able to brush off the attentions of a teen boy with grace.

In 2012 the CEO of Grünenthal Group, Harald Stock, made a very public apology for Thalidomide and the impact it had on thousands of children and families around the world. He unveiled a bronze statue of a Thalidomide child in Stolberg, the town where the company is based. Apparently, many victims of the drug were not best pleased with the gesture.

Thalidomide child statue

- In 1998 the FDA approved Thalidomide for use in cases of Multiple Myeloma. It is also used to treat leprosy and one or two other conditions.

- Some 10,000 Thalidomide babies were born world-wide.

- In the UK, of some 2,000 babies born with defects, approximately half died within a few months and 466 survived until at least 2010. In February 1968, following a legal battle, compensation (at 40% of the level of assessed damages) was paid to 62 thalidomide-affected children born in the UK by Distillers (the distributor) as a result of an initial (infant) settlement.

- The official FDA count released in the 1960s revealed that seventeen Thalidomide babies were born in the USA.

- According to a 2015 article in the Sydney Herald, “The Sydney managers of Distillers spent months sitting on damning evidence about Thalidomide’s harmful effects while the drug was still being sold, leading to thousands of avoidable deaths and injuries in Australia and overseas.”

- When the “legendary” author-journalist Sir Harold Evans died in 2020, The Guardian newspaper published a tribute highlighting one of his greatest accomplishments. While editor of The Times, Evans initiated a successful campaign to obtain compensation for the victims of Thalidomide from Distillers. You can read the tribute here.

Thanks to Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, there was no need for a massive fight in America.