Those of you who have read A Sunlit Weapon, my latest novel, may remember a small point made about the carburetor in the Merlin engine, as used on the Spitfire and Hurricane aircraft. In the early days of the war, that carburetor had a dangerous fault. When the aircraft went into a dive – a common tactic during an air-battle or dogfight if the pilot wanted to avoid being shot down – the carburetor would flood, causing the aircraft to stall. Young pilots were being killed time and time again due to this fault. For those who managed to get out of the stall – often by very quickly maneuvering the aircraft into an angle – the engine started again and a plume of black smoke would shoot out of the exhaust, which could be equally fatal because if you were in the clouds trying to avoid that German in his Messerschmitt, it would give away your position immediately. The Messerschmitt had fuel injection, so no such problem. It was aeronautical engineer Beatrice Shilling who solved the problem, and it’s likely her understanding of what to do to prevent the stall was a result of her experience in tinkering with the fuel flow on her Norton motorbike to get maximum performance when she was racing.

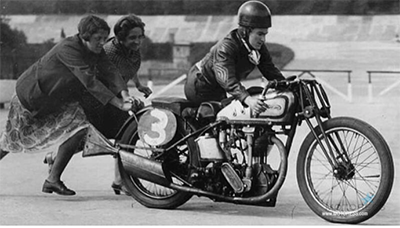

Beatrice Shilling and her Norton motorbike

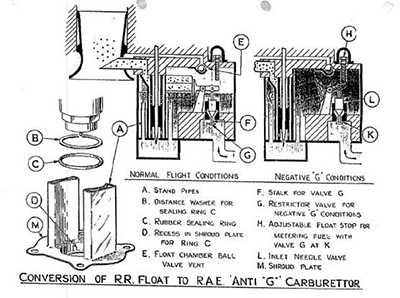

Beatrice developed a “thimble” with a hole in the center (which she later honed to become a sort of “washer”) which could be fitted to an aircraft without taking it out of service, and which immediately eliminated the carburetor problem. Pilots were ecstatic about the development. They revered the brilliant engineer and affectionately named the device, “Miss Shilling’s Orifice.”

I don’t understand it either!

So who was Beatrice Shilling?

Beatrice Shilling was born in Hampshire, England in 1909, the daughter of a butcher and his wife. Engines and speed fascinated young Beatrice, and by age 14 she had saved enough money to buy herself a motorbike, but of course she had to do all repairs herself. She was determined to become an engineer, so upon leaving school she went to work for an engineering company, fortuitously owned and run by a woman, Margaret Partridge. Margaret was an electrical engineer who was also founder of the Women’s Engineering Society and the Electrical Association for Women – both organizations were committed to opening up engineering to female apprentices. It was Margaret who encouraged young Beatrice to apply to university to study electrical engineering. Beatrice subsequently earned her BA degree in Electrical Engineering and studied for another year to become a Master of Mechanical Engineering. The only other female student studying alongside Beatrice was Sheila McGuffie, who became an aeronautical engineer and later one of the team that developed the first jet engine. Wow. And we think women engineers are a relatively new thing.

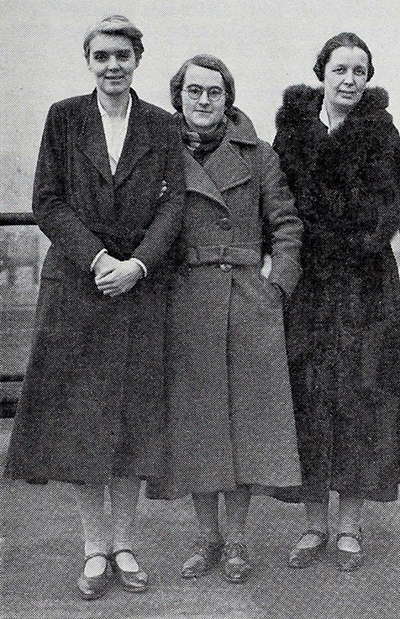

At university – Beatrice is lower right.

During this time Beatrice was also racing motorbikes, gaining her gold medal for an amazing performance at Brooklands racing circuit where she reached 106 miles per hour, chiefly due to the supercharger she had developed for her motorbike. In addition, she also raced on four wheels, driving a 1935 Lagonda at Silverstone, and later, in the 1950’s she raced sports cars at Goodwood.

Racing – and I love the fact that women are helping her get going!

With her background, her academic excellence and experience as an engineering research assistant at university, it’s hardly surprising that in 1936, she was offered a job with the Royal Aircraft Establishment. The rest, as they say, is history.

Beatrice in the middle with two other RAE aeronautical engineers, Margaret Rowbotham on the left, and Margaret Partridge on the right.

But not quite….

Given her stellar, crucial contribution to Britain’s eventual victory in WW2, Beatrice was awarded an OBE in 1947. She continued to work at the RAE until she retired in 1968 and was active in motorbike and automobile racing and the field of aeronautical engineering until she died at age 81 in 1990. In terms of her personal life, Beatrice married another aeronautical engineer, George Naylor in 1938. It is said that at first she refused his proposal, stating she would only marry him if he also achieved a gold star at Brooklands racing circuit, which he did by lapping the circuit at over 100 mph. George was with a bomber squadron during the war, and won the Distinguished Flying Cross.

It seems one element of Beatrice Shilling’s personality could have been the strike against her when it came to winning top promotions at work: she refused to play the game. She didn’t overly care for personal presentation and did not dress in smart suits (“costumes” as a matching jacket and skirt or trousers would have been known in those days) or use much, if anything, in the way of cosmetics. According to her contemporaries, she wasn’t one to go for an attractive hairstyle – or even something that tidy. And she could be a fairly blunt, no-nonsense person, which could also have set her back. But no one could deny her place in Britain’s history, her knowledge of engineering, her willingness to experiment and how she developed the simplest, most quickly implemented solution to a problem that was killing young men.

One of the toys that inspired Beatrice in childhood was a Meccano set.

A Meccano set in 1900

Meccano was the brainchild of Frank Hornby in Liverpool UK, the same man who gave us Hornby trains (I had a Hornby train set when I was a child). Something similar was invented in the USA in 1913 – the Erector set. Back in the day those toys were aimed at boys, but I’m glad to report that Meccano ads now feature girls too.

I think it’s an amazing coincidence that Beatrice’s birthday is also International Women’s Day, a fitting though quite accidental tribute to a woman who blazed a trail for women in engineering and was lauded for her contributions. According to records, her first job at the RAE was writing manuals for aircraft engines. I bet a lot of pilots – including those women of the Air Transport Auxiliary – were grateful that she had been promoted to Technical Officer in 1938, where she specialized in research and development on carburetors. Beatrice excelled in what was considered a profession for men. Her work rendered the role of fighter pilots so much safer as they took to the skies in the Spitfire and Hurricane. No wonder she became their heroine.